On 1–2 October 2025, Israeli naval forces staged a broad maritime operation against the Global Sumud Flotilla, a 40-plus vessel convoy carrying roughly 500 activists, parliamentarians, lawyers and journalists attempting to deliver symbolic humanitarian relief to Gaza. Organisers say one vessel, the Mikeno (also called Albera), reached Gaza’s territorial waters before its tracking signal was lost. Israeli forces detained scores, by some counts more than 200, by others over 300, and redirected seized vessels to Ashdod. The operation has prompted urgent diplomatic protests, criminal probes (notably from Turkiye), rights-group condemnation and fresh legal debates over blockades, jurisdiction and the use of force at sea.

What happened at sea, the facts reporters can establish:

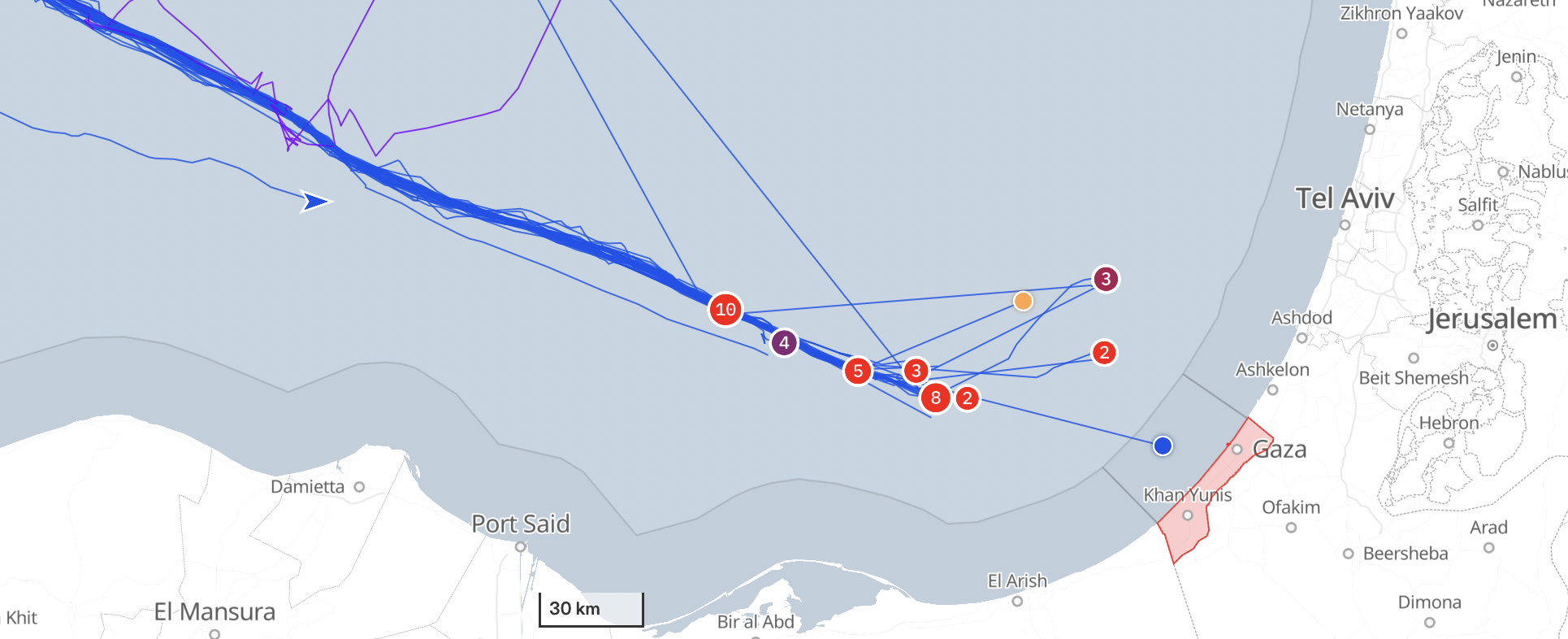

- Large naval cordon and communications disruption. Flotilla trackers and live streams indicate the convoy was encircled by roughly 20 Israeli warships; organisers and journalists aboard reported systematic communications jamming and the disabling of cameras on multiple vessels. Activists described being forced to sail in dispersed, vulnerable parcels as the navy “cut the convoy’s connective tissue.”

- Detentions and redirections. Organisers initially reported 223 detainees; later counts and organisational trackers put the number higher (some reports say ~317). Seized vessels were redirected to Ashdod for inspection and deportation processing. Israel’s Foreign Ministry posted that detainees would be taken to Ashdod and deported.

- A vessel near Gaza — Mikeno: Multiple trackers and flotilla officials show the Mikeno approaching Gaza waters and then losing its signal at about 9.3 nautical miles from shore. Organisers and onboard reporters said contact was lost for hours; Israeli spokespeople told media no vessel made it through. Whether Mikeno was towed, boarded, disabled, or simply switched off its transponder is central and unresolved.

- Tactics reported by activists: live and recorded footage shared by activists and media showed crews donning life jackets, being hosed by water-cannon, and in some cases forcibly boarded by armed personnel. Flotilla organisers accused Israeli boats of ramming and seizing cameras and equipment. Israel maintains the operation was a lawful enforcement of a blockade and that its forces offered an alternative, transfer of aid through established land crossings.

Eyewitness Testimony, Official Statements And Organisational Responses Flotilla Organisers / Onboard Journalists:

- “High Alert. Our vessels are being illegally intercepted. Cameras are offline, and vessels have been boarded by military personnel,” the convoy’s communications account posted as interdictions began. Activists repeatedly reported jamming and loss of livestream capability.

Al Jazeera (reporting from aboard a flotilla boat):

- Al Jazeera’s Hassan Masoud identified Mikeno as the ship that reached Gaza waters and said contact was lost for more than seven hours; he described the event as “unprecedented.”

Israel (official line):

- Israel defended the interdictions as enforcement of a “lawful naval blockade” and said detainees would be processed in Ashdod, arguing the flotilla was approaching an active combat zone and that safer alternatives had been offered. Israeli officials posted images and short clips of boarded activists to underline their account.

National Government Reactions:

- South Africa (President Cyril Ramaphosa): called the seizure a “grave offence” and demanded the immediate release of detainees, including Nkosi Zwelivelile “Mandla” Mandela. Ramaphosa tied the incident to South Africa’s ICJ case against Israel and said the interceptions contradict international norms.

- Türkiye (Foreign Ministry): labelled Israel’s action “an act of terrorism” and opened a criminal probe after Turkish nationals were detained. Turkey’s statement framed the interdiction as a grave violation of international law.

- Amnesty International: urged states to protect the flotilla and warned that blocking humanitarian missions would breach humanitarian principles and international law. Amnesty called on governments to “step up pressure to protect the flotilla.”

Media & NGOs on the scene:

- Journalists aboard ships reported forced confiscation of camera equipment, and human-rights groups on standby said lawyers aboard were meticulously documenting each boarding and seizure to file complaints with the UN and ICJ.

Investigative Analysis, Tactics, Patterns And The Evidence That Demands Scrutiny:

1) Communications blackouts, deliberate tactic or expected collateral?

Multiple independent trackers and ship feeds show coordinated signal loss and jamming on several boats at the moment Israeli vessels closed in. Activists and onboard lawyers reported that jamming preceded boardings and confiscations of recording devices, a pattern identical to past flotilla intercepts and to tactics documented in other maritime interdictions (2010 Mavi Marmara and later incidents). If the jamming was deliberate, it would be a premeditated effort to remove independent witnesses and evidence, a fact with serious legal and accountability implications.

2) Use of non-lethal but coercive means, water cannon, ramming, and seizures.

Videos and multiple activist testimonies show water-cannon, alleged ramming attempts, and fast-boat boarding operations. These are coercive measures that can be lawful in narrow circumstances (self-defence, preventing smuggling) but become unlawful when disproportionate, directed at civilian vessels, or employed in international waters without legal jurisdiction. The recurring allegation that cameras were disabled and equipment seized adds to a pattern of controlling the narrative and preventing independent scrutiny.

3) Jurisdictional Fog: International Waters Vs. Territorial Waters.

The legal crux is whether the interdictions occurred in international waters or within a legitimately declared and effective blockade around Gaza. The flotilla reports most incidents in international waters (~70–120 nautical miles out), with Mikeno reportedly much closer, roughly 9–30 nautical miles from Gaza. Under UNCLOS and customary law, a blockade can be enforced on the high seas if it has been lawfully declared and is effective, but such enforcement still requires strict proportionality and safeguards for civilians. The factual dispute over the Mikeno’s final position, and what happened when its signal disappeared, is therefore decisive.

4) Pattern of escalation and political signalling.

This operation was large, visible and timed during intense global scrutiny of the Gaza crisis. The scale (40+ vessels), presence of high-profile figures (Greta Thunberg, members of parliaments, journalists), and the choice to detain many nationals from dozens of states have immediate diplomatic consequences, from Colombia’s expulsion moves to Turkey’s criminal probe and South Africa’s ICJ posture. The interdiction is as much a political act as a security operation: it signals Israel’s determination to maintain the maritime chokehold and deter future solidarity missions.

The Legal Landscape: Precedents, Claims And Where This Could Go.

- Palmer & Mavi Marmara (2010): The 2010 raid produced a mixed record: the Palmer Report found a lawful blockade but criticised excessive force; UN experts and others have disputed that conclusion. The 2010 precedent shows courts and commissions split: legality of a blockade can be argued, but the use of force and detention practices face far tougher scrutiny.

- UNCLOS and high seas enforcement: A state may intercept vessels on the high seas under narrow conditions (e.g., piracy, slave trade, or to enforce an effective blockade), but routine interception of humanitarian civilian missions invokes high thresholds for lawfulness. If the flotilla was in international waters and unarmed, the forced boarding and mass detention risk breaching maritime law and human rights obligations. Legal experts have already flagged that “whether the IDF intercepted the Mikeno in international waters is crucial.”

- ICJ implication: South Africa’s public linking of the interdiction to its ICJ case, and its labelling of the seizure a “grave offence”, raises the prospect that material seized, witness statements, and detainee testimonies will form part of broader litigation and fact-finding on Israel’s conduct in Gaza.

Voices On The Record (Selected Quotes):

- “High Alert. Our vessels are being illegally intercepted. Cameras are offline, and vessels have been boarded by military personnel,” the flotilla’s public account warned as raids began.

- Turkey’s MFA: “The attack carried out by Israeli forces in international waters … constitutes an act of terrorism that gravely violates international law.”

- South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa: the seizure was a “grave offence” against global solidarity and must be reversed.

- Amnesty International (on X): states “must step up pressure to protect the flotilla” and stressed that “any attempt to block it is an attack on humanitarian principles.”

- Reuters summarised legal worries bluntly: “Multiple vessels … were illegally intercepted and boarded by Israeli Occupation Forces in international waters,” organisers said, a phrase likely to be central in any later legal complaints.

What Still Needs Independent Verification (And Why It Matters).

- Mikeno’s fate. Was the Mikeno boarded in Gaza waters, towed, or did it deliberately switch off transponders? Independent AIS data, AIS aggregator logs and onboard testimony (and any Israeli operational record) are essential to establish whether a vessel actually reached Palestinian territorial waters and whether Israeli forces then acted within or outside legal limits.

- Exact location of each interception. Ship-tracking logs and independent maritime monitoring (e.g., satellite AIS, coastal radars, third-party observers) are needed to determine whether most interdictions were on the high seas or within a declared exclusion zone. This governs whether UNCLOS or blockade law applies.

- Chain of custody for evidence and the treatment of detainees. Activists’ claims of confiscated cameras and jammed footage need cross-checking against what Israel retained, what was destroyed or erased, and how detainees were processed, since suppression of evidence would amount to deliberate obstruction of future legal inquiries.

- Rules of engagement and proportionality. Any use of force must be examined against Israeli rules of engagement and the proportionality principle of international humanitarian law. Were stun devices, water cannon, or ramming employed in ways that endangered civilians? Independent medical and forensic documentation will matter.

Consequences: Diplomacy, Law And The Information War.

The interdiction has already produced immediate diplomatic fallout (summons, expulsions, criminal probes). But the deeper consequences will be legal and informational:

- Legal: Expect complaints to the ICJ, national criminal probes (e.g., Turkey), and filings relying on detainee testimonies and documented seizures. Evidence control (who holds footage, logs, and chain-of-custody documentation) will be decisive.

- Political: The operation strengthens arguments by those who say Israel will use force to maintain the siege at all costs, and it hardens public opinion in many countries, intensifying protests and diplomatic rows.

- Information: Cutting cameras and jamming comms is not just a tactical move, it’s an attempt to control the narrative. If true, it replicates a pattern seen in earlier flotillas where independent documentation contradicted official accounts and became central evidence.

Recommended Next Steps For Watchdogs, Journalists And Investigators:

- Preserve independent AIS and satellite data for every vessel (timestamped and geolocated). Cross-compare commercial AIS aggregators and the flotilla’s own tracker.

- Secure custody of activists’ devices and metadata (photos, videos, timestamps) before evidence is wiped or declared “lost.” Lawyers aboard the flotilla say they are already documenting boardings; these records must be treated as a fragile chain of evidence.

- Interview detainees immediately once released — medical checks, sworn statements, and forensic copies of any materials seized by Israeli forces.

- Press for third-party observers (UN, ICRC) to get access to Ashdod processing centres and to the flotilla vessels still at sea.

- Legal action: NGOs should prepare preliminary filings to international bodies while preserving the rights of detainees not to be deported before testimony can be taken.

Selected Primary Sources And Reporting Used In This Investigation:

(Representative selection — full archive and raw tracker logs should be secured by investigators.)

- Al Jazeera — live reporting from onboard and desk coverage of flotilla interdiction.

- AP — “Israeli navy intercepts most flotilla boats and arrests activists.” AP News

- Reuters — reporting on detentions and international reactions (South Africa, Turkey).

- The Guardian — rolling coverage and eyewitness accounts from the flotilla.

- Amnesty International — public statements calling for protection of the flotilla and warning of law violations.

- Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs — official condemnation (“act of terrorism”).

- Newsweek / maritime trackers — vessel-level AIS reporting on Mikeno and other boats.

Timeline: Interception Of The Global Sumud Flotilla (1–2 October 2025).

Wednesday, 1 October 2025

Morning – Early Afternoon (GMT+3, Eastern Mediterranean)

- Flotilla vessels, around 40 ships, carrying ~500 activists, MPs, lawyers, journalists, depart from staging areas in international waters, heading toward Gaza.

- Communications feeds show vessels moving in loose formation. Activists report Israeli navy vessels shadowing at a distance.

(Sources: flotilla organisers’ tracker, Al Jazeera live feed).

~15:00–16:00

- Organisers warn of increased naval presence: at least 20 Israeli warships are sighted.

- First reports of jamming and loss of livestreams from multiple ships; activists post urgent messages that “cameras are offline.”

(Sources: flotilla comms posts, Guardian live updates).

16:30–17:00

- Initial boardings begin. Smaller vessels are approached, boarded by armed personnel, and forced off course.

- Organisers issue “High Alert” post: “Our vessels are being illegally intercepted.”

(Sources: flotilla media team, Reuters).

18:00–19:00

- Water cannon and ramming tactics reported. Video clips (later uploaded after detentions) show Israeli boats manoeuvring aggressively, forcing some flotilla ships to halt.

- Journalists report confiscation of cameras and phones during boardings.

(Sources: eyewitness footage, Guardian, Amnesty statements).

19:30–20:30

- Most flotilla vessels are now under Israeli control and redirected north toward Ashdod port.

- Organisers report hundreds detained. Initial counts: 223. Later revised upward (~317).

(Sources: AP, flotilla organisers, Israeli FM statement).

Thursday, 2 October 2025

00:00–02:00

- Mikeno (Albera) continues toward Gaza. Unlike others, it maintains course until ~9.3 nautical miles off Gaza.

- Al Jazeera correspondent Hassan Masoud reports contact with Mikeno was lost for over seven hours after approaching Gaza’s territorial waters.

- Speculation rises that Mikeno may have entered Gaza’s 12-nautical-mile limit before being seized or its transponder disabled.

(Sources: Al Jazeera, flotilla tracker, Newsweek AIS logs).

~03:00–04:00

- Israeli sources claim all vessels have been intercepted, denying any made it through to Gaza.

- No independent confirmation on Mikeno’s final status, whether boarded at sea, towed away, or forcibly shut down.

(Sources: Israeli government statements, Reuters).

Morning–Afternoon

- Detainees processed in Ashdod. Israel confirms activists will be deported.

- Reports emerge of detainees being held without access to lawyers or consular officials in the first hours.

- Amnesty International and lawyers’ groups issue urgent calls for independent access.

(Sources: Amnesty International, flotilla lawyers’ statements).

Throughout the Day

- International reactions escalate:

- Türkiye announces a criminal investigation, calling the interdiction “an act of terrorism.”

- South Africa condemns the detention of Mandla Mandela, calling the seizure a “grave offence.”

- Colombia summons Israel’s ambassador and considers expulsion.

(Sources: Turkish MFA, Ramaphosa statement, Reuters).

Unresolved Key Points:

- Mikeno’s fate — Did it cross into Gaza’s territorial waters? Was it boarded inside or outside the 12 nm limit? This is central to legal challenges.

- Exact number of detainees — Organisers’ higher count (~317) vs Israel’s reported ~223.

- Treatment of detainees — Reports of camera seizures, restricted legal access, and possible evidence destruction remain unverified.

- Rules of engagement — Were ramming/water cannon proportionate, and were weapons beyond “non-lethal” used?

Conclusion: Why This Matters Beyond Symbolism.

The interception of the Global Sumud Flotilla marks not just another episode in Israel’s 20-year-old blockade of Gaza, and prior, but a dangerous escalation in the confrontation between international civil society and state power. Unlike previous flotillas, the Mikeno reportedly crossed into Gaza’s territorial waters before its signal was lost, suggesting Israel may have conducted a military seizure inside Palestinian waters, a move that international maritime lawyers describe as “a textbook act of piracy” and “an act of terrorism.” The deliberate ambiguity surrounding its fate is no accident. For years, Israel has relied on communication blackouts, confiscated cameras, and detention without consular access to suppress evidence of misconduct at sea and the violation of the UN charter, international and maritime laws.

This was not merely another headline stunt. The Global Sumud Flotilla attempted, at scale and with international figures aboard, to force a test of maritime, humanitarian and human-rights norms around Gaza. The evidence collected so far points to a deliberate, multi-layered interdiction strategy: jamming and cutting communications, rapid boarding, mass detention, equipment seizure and immediate deportation. Those tactics raise urgent questions about compliance with international law, the right to deliver humanitarian aid, and the ability of neutral witnesses to preserve evidence.

If the Mikeno truly entered Gaza waters, the legal and political stakes rise: the incident could become proof that civil disobedience at sea can, under certain conditions, breach the siege, and that states will use overwhelming force to prevent that precedent. If it did not, then the operation is nonetheless a test case in how modern navies can police, isolate and control humanitarian action by neutral civil society, with significant implications for future aid, accountability and the protection of civilians.

The scale of the raid, 40 ships, 300 passengers from 45 countries, including MPs, lawyers, and journalists, is unprecedented in global solidarity movements. Rights groups say the tactics used, ramming, water cannons, and mass detention, cannot be justified as “security enforcement.” “This was not law enforcement, it was maritime repression,” said flotilla lawyer Arne Birkenstock, deported after 48 hours in custody. Amnesty International stressed the convoy was unarmed and publicly declared its mission. Human Rights Watch warned: “What Israel is criminalising is not weapons, but witnesses.”

The international fallout underscores the gravity. Türkiye has opened a criminal investigation, calling the raid “an act of terrorism.” South Africa has accused Israel of “abduction” after the detention of MP Mandla Mandela. Spain and Malaysia have demanded answers, with 23 Malaysians still in custody at the time of writing. Analysts warn that this marks the “extraterritorialisation of the Gaza siege”, the extension of a blockade into international waters, ensnaring the citizens of sovereign states. “When Spain’s lawyers, South Africa’s MPs and Malaysia’s journalists can be seized on the high seas, the siege ceases to be Gaza’s alone,” said Dr. Karim El-Haddad, an international law scholar in Geneva. “It becomes a global legal crisis.”

The larger legal and moral question is unavoidable: if unarmed civilians carrying flour and insulin are met with warships, then what remains of the international community’s duty to prevent starvation in Gaza? The ICJ has already ruled Israel’s occupation unlawful; flotilla lawyers now prepare to submit evidence of maritime crimes and collective punishment. Whether those findings translate into accountability is uncertain, but the case is moving onto international legal terrain that Israel cannot fully control.

What is certain is that the Sumud Flotilla has already punctured Israel’s narrative. It exposed the blockade for what the UN has repeatedly called it: collective punishment. As one South African activist livestreamed before her feed went dark: “If a ship carrying bread and medicine is treated as a threat, then the real threat Israel fears is not weapons, it is solidarity.”

The flotilla may not have broken the siege in physical terms, but it has broken the illusion of its legality. By forcing governments to respond, by raising evidence for future courts, and by showing the extraordinary lengths to which the siege is upheld, it has turned a single maritime raid into a global indictment of the blockade itself.

“If unarmed civilians carrying humanitarian aid are met with armed naval attacks in international waters, what does this say about Israel’s commitment to international law, the protection of civilians, and the legitimacy of the blockade itself?”