Original Article Date Published:

Article Date Modified:

Help support our mission—donate today and be the change. Every contribution goes directly toward driving real impact for the cause we believe in.

For the most vulnerable people in society, the elderly pensioners facing a prolonged stay in hospital, the moment of discharge should signal relief and recovery. Instead, for thousands born before 1959, it is increasingly becoming the start of a financial emergency.

Buried within the rulebook of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is a policy that suspends crucial disability and income top-up benefits once a hospital stay exceeds 28 days. Officials describe it as a safeguard against “double provision” of public funds. But growing evidence suggests the rule is creating hardship so severe that some pensioners struggle not only to recover, but to survive.

In a country that promises cradle-to-grave care, the question is stark: why is the state tightening the purse strings precisely when illness has already taken its toll?

The Mechanics Of The Suspension:

The core State Pension continues during hospital stays.

But two lifelines are placed in jeopardy:

- Pension Credit – a means-tested top-up guaranteeing a minimum weekly income.

- Attendance Allowance – a tax-free payment for pensioners needing help with personal care.

Once hospitalisation exceeds 28 days, Attendance Allowance stops. The disability elements attached to Pension Credit are often reduced or removed.

The official reasoning: the state is already covering food, heating, and care costs within the hospital.

But this narrow accounting view ignores what happens next.

From Bedside To Bankruptcy: The Recovery Penalty.

Patients discharged after prolonged stays are often weaker, more vulnerable, and more dependent on support than before admission.

They return home to:

- Increased heating costs due to frailty.

- Higher laundry and hygiene expenses.

- Taxi fares for follow-up appointments.

- Temporary private care.

- Nutritional supplements are not covered by the NHS.

Yet this is precisely when Attendance Allowance may have been cut.

Advisers describe what follows as a “recovery penalty”, a financial cliff-edge at the point of discharge.

More disturbingly, some pensioners report delaying physiotherapy, rationing food, or skipping private care hours because their income has been reduced. In extreme cases, individuals already living at the subsistence level face choices between heating and adequate nutrition during recovery.

Financial curtailment does not simply cause inconvenience. It can compromise recovery outcomes.

For elderly stroke survivors or heart patients, insufficient heating can worsen cardiovascular strain. Inadequate nutrition delays wound healing. Reduced care hours increase fall risks.

When financial insecurity interferes with rehabilitation, it becomes a public health issue—not merely an accounting adjustment.

The Struggle For Treatment And Survival:

Critics argue the rule creates a cruel paradox: the state funds acute hospital treatment but undermines the conditions necessary for recovery outside hospital walls.

Pensioners on low incomes often rely on Attendance Allowance to:

- Pay carers who assist with medication management.

- Fund transport to outpatient appointments.

- Maintain dietary requirements.

- Keep homes adequately heated during convalescence.

When that support is suspended, some struggle to afford the very measures that prevent readmission.

The absurdity lies in the circular cost.

If financial hardship leads to complications or relapse, the NHS may bear the far greater expense of emergency readmission. What is presented as fiscal prudence risks becoming fiscal short-sightedness.

At its harshest edge, the rule effectively conditions recovery on liquidity.

Illness should not become a trigger for financial triage. Yet for the poorest pensioners, hospitalisation can now destabilise the fragile equilibrium that keeps them housed, fed, and warm.

Administrative Burden On The Sick:

The DWP requires hospital stays, even of a single night, to be reported immediately. Detailed information must be provided. Delays can result in overpayment recovery or investigation.

There is no automatic NHS–DWP data-sharing system. The responsibility rests on elderly patients or relatives to navigate bureaucratic channels during a medical crisis.

For a pensioner recovering from surgery or cognitive impairment, this expectation borders on unrealistic.

Failure to notify promptly can lead to clawbacks that further deepen hardship, sometimes months after discharge.

An Outdated Rule In A Modern System:

The 28-day rule reflects an era when hospital stays were longer and community rehabilitation pathways less complex.

Today:

- Patients move through acute wards, step-down facilities, and rehabilitation centres.

- Hospital discharge is accelerated under bed pressure.

- Community care relies heavily on benefit-funded top-ups.

Yet time spent in rehabilitation still counts toward the 28-day threshold.

The system does not distinguish between acute treatment and transitional recovery settings.

The National Insurance Irony:

Under rules administered by HM Revenue & Customs, older pensioners have been urged to fill gaps in National Insurance records to increase their State Pension entitlement.

But even those who invest hundreds of pounds to improve retirement income remain vulnerable to means-tested reductions if hospitalised.

One arm of government encourages pension maximisation. Another suspends supplementary support during illness.

The contradiction is glaring.

A Poverty Penalty:

The rule’s impact falls overwhelmingly on those reliant on means-tested support.

Pensioners with private pensions or savings see little disruption.

Those living solely on state-backed income experience sudden reductions.

In effect, the poorest are most exposed to the consequences of illness.

The rule does not apply evenly; it bites hardest where resilience is lowest.

A False Economy?

If financial hardship delays discharge planning or contributes to readmission, the savings generated by suspending Attendance Allowance may be dwarfed by NHS costs.

Economically, socially, and ethically, critics argue the policy is ill-conceived.

Illness should not trigger destitution.

Recovery should not depend on liquidity.

A safety net should not retract at the moment of greatest vulnerability.

What Pensioners Must Do:

Until reform occurs, experts advise:

- Report hospital stays immediately.

- Arrange for an appointee if possible.

- Re-notify upon discharge.

- Seek welfare advice promptly if payments are reduced.

A System At Odds With Itself:

The 28-day rule may have been drafted as an administrative safeguard.

But in practice, it functions as a blunt instrument, one that risks pushing frail pensioners into hardship precisely when resilience is lowest.

At a time when Britain’s population is ageing, and healthcare pressures are mounting, a policy that complicates recovery and destabilises finances raises a troubling question:

Is fiscal discipline being pursued at the expense of human dignity?

For many of Britain’s oldest citizens, the danger is not abstract.

It is felt in colder homes, thinner meals, delayed care, and the quiet anxiety that illness may cost more than health alone.

Conclusion: When The Safety Net Becomes A Tripwire.

The 28-day rule is often defended as a matter of administrative tidiness. But after examining its real-world consequences, that defence begins to look less like prudence and more like indifference.

At its core, this is not simply a bureaucratic adjustment. It is a structural contradiction.

The British state funds life-saving hospital treatment through the NHS, yet simultaneously withdraws the modest income supports that make recovery possible once a patient leaves the ward. The same government that urges older citizens to strengthen their retirement finances through National Insurance top-ups permits a mechanism that can instantly erode those gains during illness.

This is not joined-up governance. It is policy fragmentation with human consequences.

For the poorest pensioners, the 28-day rule functions as a hidden vulnerability test. Fall ill for too long, and your financial stability is reassessed. Require extended care, and your income is reduced. Need longer rehabilitation because of the severity of your condition, and you are penalised for it.

The logic is perverse: the more serious your illness, the greater the financial risk.

Investigative scrutiny suggests the rule disproportionately impacts those who already have the least financial resilience. Pensioners with private pensions or savings remain largely insulated. Those reliant on means-tested support, often women, the widowed, the disabled, and lifelong low earners, absorb the shock.

In effect, illness becomes a filter that exposes poverty.

The state argues that hospital care covers “living costs.” But hospital treatment does not eliminate rent or mortgage payments. It does not heat an empty home in winter. It does not maintain direct debits, insurance policies, council tax obligations, or household standing charges. Nor does it account for the surge of costs that follow discharge, transport, rehabilitation aids, nutritional supplements, or temporary care.

By treating hospitalisation as a suspension of financial need, the system reduces human vulnerability to a line item.

More troubling still is the absence of automatic coordination between the NHS and the DWP. In a digitised government ecosystem, the burden of compliance remains squarely on the shoulders of the unwell. The frail must self-report. The cognitively impaired must navigate helplines. Families must decode regulations while managing a medical crisis.

Administrative efficiency is being extracted from those least able to provide it.

From a public finance perspective, the savings achieved by suspending Attendance Allowance for several weeks may be negligible when set against the cost of delayed discharges or hospital readmissions triggered by inadequate home support. If even a fraction of patients relapse due to insufficient post-discharge stability, the rule risks becoming not just ethically questionable, but economically irrational.

Ultimately, the 28-day rule reveals a deeper tension in the modern welfare state: whether fiscal discipline is being pursued in isolation from social outcomes.

A safety net is meant to catch people when they fall. Under this policy, falling ill can cause the net itself to fray.

For Britain’s oldest and sickest citizens, the issue is not theoretical. It is measured in heating left unused, care hours reduced, recovery slowed, and anxiety compounded. Illness is already destabilising. To layer financial insecurity on top of physical vulnerability is not merely harsh; it is illogical.

If a welfare system withdraws support at the point of maximum need, it ceases to function as protection. It becomes a tripwire.

And that raises a fundamental question for policymakers:

Is the purpose of social security to manage budgets, or to safeguard dignity when health fails?

For the most vulnerable people in society, the elderly pensioners facing a prolonged stay in

AFRICA/DARFUR – Clashes erupted over the weekend in the strategic border town of Tina (also

In the waning days of 2025, as global financial publications released their annual rankings, a

BIRMINGHAM/SMETHWICK, UK – A murder investigation has been launched after a young man was fatally

Mike Huckabee’s statements to Tucker Carlson reveal a systematic alignment of US diplomacy with maximalist

LINCOLN, UK – Stephen Conway, the Bishop of Lincoln, was arrested by Lincolnshire Police on

In a landmark 6–3 ruling that reasserted Congress’s constitutional control over taxation, the US Supreme

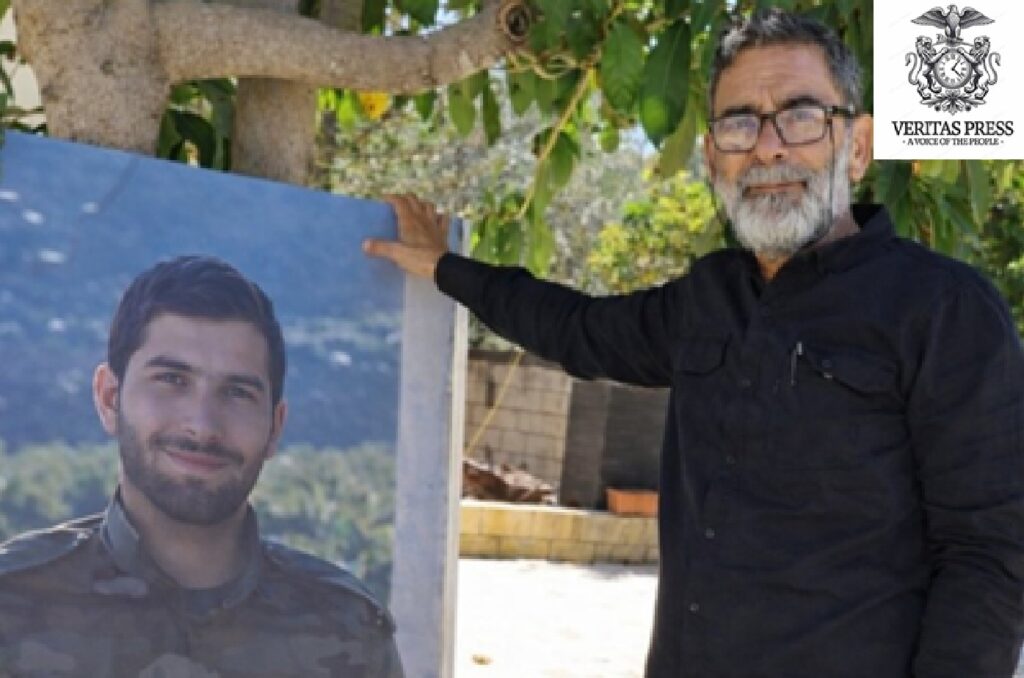

In the border village of Tallousa in southern Lebanon, 62-year-old Ahmed Turmus received a phone

The first Friday of Ramadan at Al-Aqsa Mosque has always been a barometer for tensions

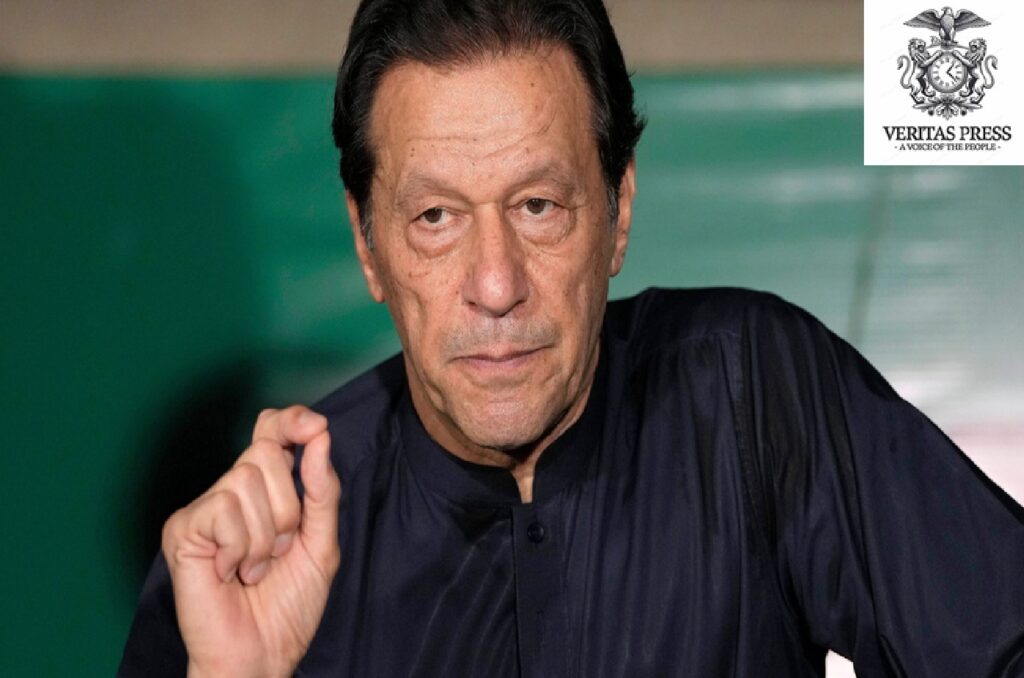

A growing international outcry over the health of jailed former Pakistani prime minister Imran Khan