Title: Under Rubble And Candlelight: Gaza’s Christmas After Genocide.

Press Release: Veritas Press C.I.C.

Author: Kamran Faqir

Article Date Published: 24 Dec 2025 at 17:50 GMT

Category: Middle-East | Palestine-Gaza-West Bank | Under Rubble And Candlelight: Gaza’s Christmas After Genocide.

Source(s): Veritas Press C.I.C. | Multi News Agencies

Website: www.veritaspress.co.uk

Business Ads

How Israel’s genocidal war has transformed Christmas into a testament of endurance, loss, and political crisis

Gaza’s Christmas this year is not a celebration. It is a sacred act of survival, performed under rubble, flanked by displacement camps, intermittently lit by candlelight, and suffused with the grief of families who have lost loved ones and homes.

Outside Holy Family Church in Gaza City, the only Catholic church in the Strip, there are no festive lights, no choirs, no bells. Instead, hundreds of displaced civilians squeeze into damaged corridors and cold halls, seeking shelter, warmth, and a semblance of community amid the ruins of a city that has been under near-constant bombardment for more than two years.

A Christmas Of Ruin, Scarcity, And Survival:

Father Gabriel Romanelli, the parish priest at Holy Family, describes what this Christmas has become: “We won’t have outdoor celebrations, like lights or dancing… the war is still going on. This ceasefire has improved the situation, but the war continues in other ways, depriving people of the assistance they need.”

Romanelli’s words are not abstract theology; they are grounded in the total collapse of basic infrastructure in Gaza. Electrical grids are non-functional, water systems destroyed, medical facilities overwhelmed or shuttered, and half of essential medicines are absent, according to UN observers cited in reporting from inside Gaza.

Attallah Tarazi, 76, who has survived by sheltering inside the church compound for more than two years, summed up the contradictions of this Christmas: “I feel like our joy over Christ’s birth must surpass all the bitterness that we’ve been through,” yet admits that traditional celebration feels impossible amid ongoing trauma and loss.

Families still grieving expressed profound sorrow. One Gaza resident, forced to rebuild his life inside the compound after an Israeli sniper killed his mother and sister, told The National that “there is nothing to celebrate… the wound is still deep.” His 12-year-old daughter Maryam yearns for a return to lights, songs and the warmth of community that Christmas once brought, but “the war and Israel took all that happiness from us.”

This year’s fragile truce has eased bombardment, but it has not reversed Gaza’s destruction. Explosions, albeit less frequent, can still be heard near the parish grounds, and many displaced people continue to live in tents that offer little protection from cold, rain, and disease.

The war’s toll on Gaza’s Christian community, including Orthodox and Catholic residents, has been catastrophic. Once numbering over a thousand, only a few hundred families now remain. Most lost homes, livelihoods, or fled abroad. Church leaders note that Gaza’s Christians are at risk of becoming an almost vanished community, a fact laden with spiritual and cultural loss.

Cardinal Pizzaballa’s Visit: Solidarity Or Media Gesture?

In the days before Christmas, Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem Cardinal Pierbattista Pizzaballa made a rare pastoral visit to Holy Family Church, a gesture covered widely in international media.

The patriarch was greeted by children wearing Santa hats and keffiyehs, a symbolic fusion of Christmas tradition and Palestinian identity, as he presided over liturgies designed to bolster faith amid despair. Yet even this visit underscored an uncomfortable truth: church leaders now perform pastoral care in a war zone where the very presence of places of worship has been repeatedly imperilled.

Last June, Holy Family’s compound was struck by Israeli shell fragments while families sheltered inside. Three people died, and several were wounded, including the parish priest, a trauma that still haunts survivors.

Cardinal Pizzaballa has called on Gazans to “rebuild life” and carry the Christmas spirit forward, but his words echo in empty streets where businesses have vanished, and families have lost everything.

Beyond Gaza: Bethlehem And The Collapse Of Religious Tourism.

Meanwhile, in Bethlehem, the symbolic birthplace of Christ, Christmas has surfaced cautiously, but not without a sobering context. Thousands gathered for the tree lighting and Mass, a sign of resilience and hope, yet the celebration is dramatically muted compared with past years.

Bethlehem’s economy, once propelled by religious tourism, now teeters on collapse. The Bethlehem Chamber of Commerce estimates more than $1 billion in direct losses due to the long-running war’s impact on tourism, hotel closures, and shuttered commerce.

Dr. Samir Habboon, the chamber’s president, warned that the national income of Palestine has been halved, with tourism’s contribution to GDP plunging and labour markets shattered.

Long-term trends point to structural devastation. A special bulletin from the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics shows that Gaza’s GDP shrank by 84% compared to pre-war levels, while the West Bank recorded a marginal contraction. Construction, industry, and services sectors tied to daily life have collapsed across Gaza.

In Bethlehem, unemployment, already high before the war, has soared. CNEWA’s regional director noted that approximately 31% of residents are jobless, and tourism revenues, once measured in millions, now stagnate.

Local craftspeople describe a slow death of heritage industries. One olive-wood artisan told reporters that sales have evaporated, and cultural traditions once sustained by religious tourism risk disappearing entirely.

A young resident in Nativity Square crystallised the contradiction of this season: “We light the tree and sing, but many of us know that Christmas here is now a prayer for Gaza, not a festival.”

Voices From The Ground: Palestinian Christians And Activists.

Palestinian civil society voices emphasise that Gaza’s Christmas reflects a broader political crisis. Activists with aid and rights organisations argue that framing this as a solely “spiritual test” ignores the ongoing siege, apartheid infrastructure, and discriminatory policies that have exacerbated suffering. They note that international humanitarian law requires the protection of civilians and places of worship, protections repeatedly violated in Gaza. (Human rights reports, ongoing)

Local Muslim and Christian solidarity groups in the West Bank have also joined calls for global accountability, staging vigils and interfaith prayers that explicitly connect Christmas observance with demands for an end to the blockade, bombardment, and occupation.

Conclusion: Christmas As Evidence, Not Metaphor.

This Christmas in Palestine is no longer symbolic. It is evidentiary.

In Gaza, the absence of celebration is not a matter of faith tested by hardship, but the consequence of civilian life systematically dismantled. Churches functioning as displacement camps, children marking Christmas without food, warmth, or safety, and priests describing survival as their primary mission are not tragic anomalies; they are the predictable outcomes of a prolonged siege and a war waged with near-total impunity.

As Palestinian theologian and activist Rev. Dr. Mitri Raheb has long argued, “Faith under occupation cannot be separated from justice. To spiritualise suffering without naming its cause is to become complicit in it.”Gaza’s Christmas makes that warning unavoidable. When Mass is held under shattered roofs, when candles replace electricity, and when churches substitute for homes, the line between humanitarian crisis and political crime is no longer blurred; it is exposed.

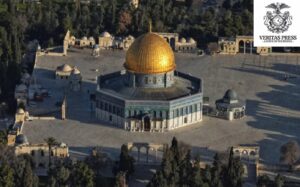

Yet Israel’s crimes in Gaza cannot be reduced to an assault on religious communities alone. They are not sectarian; they are structural. What is unfolding is not a war on Christianity or Islam, but a campaign of ethnic cleansing and absolute control, driven by a Zionist project that seeks full dominance over the occupied Palestinian territories, Gaza, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem alike. Churches are struck not because they are churches, but because Palestinians are inside them. Mosques, hospitals, schools, bakeries, and refugee camps meet the same fate for the same reason: they stand in the way of territorial domination and demographic erasure.

International church institutions have issued statements of concern, prayer, and solidarity. Yet Palestinian Christians continue to ask why moral language has not translated into material pressure. Why has the destruction of one of the world’s oldest Christian communities failed to provoke meaningful political consequences? As one volunteer sheltering families at Holy Family Church told El País: “We don’t need more words about peace. We need protection. We need food. We need this to stop.”

In Bethlehem, the cautious return of Christmas does not signal recovery. It signals resistance under suffocation. Tree lightings, Mass, and pilgrimage unfold amid economic collapse, mass unemployment, and Israeli military closures that choke movement and livelihoods. Tourism, once the backbone of the city, has been deliberately strangled, workshops shuttered, cultural heritage eroded, and families pushed into poverty.

Yet Bethlehem’s response has been collective and political. Celebrations were unified and restrained. As Father Hanna Salem explained, lighting a single Christmas tree was a declaration: “We want to deliver a powerful message reflecting our solidarity as Palestinians, whether Muslim or Christian, and show the world that we live together as one nation.”

This unity underscores a deeper reality: Palestinian suffering is not divided along religious lines. Gaza’s starvation, Bethlehem’s economic strangulation, and the West Bank’s accelerating settlement expansion are interconnected components of the same system, one designed to fragment, displace, and ultimately remove Palestinians from their land.

Analysts and rights organisations increasingly describe this system as one of settler-colonial domination, where violence, blockade, legal discrimination, and economic collapse function together to consolidate Israeli control. The war in Gaza did not erupt in isolation; it intensified a long-running project of dispossession that now threatens the very continuity of Palestinian life across historic Palestine.

For Palestinian Christians, Christmas has therefore shifted in meaning. It is no longer primarily about incarnation, but about presence. Lighting a candle in Gaza, reopening a workshop in Bethlehem, or praying beneath a damaged church roof has become an act of defiance: we are still here.

As Father Issa Thalji of the Church of the Nativity put it, “Hope is the daily bread. We must hold on to spirituality that restores our refuge, where healing from cruelty happens.” But Palestinians are clear: hope divorced from justice is hollow.

This Christmas, Gaza does not ask the world for sympathy. It demands reckoning. Beneath the candlelight and prayers lies a question no hymn can silence:

Will the world continue to commemorate Christmas in the land of its birth while allowing the systematic erasure of its people, and the consolidation of absolute control over their land, to proceed unchecked?