ISLAMABAD — As the skies continue to pour over Pakistan’s fractured terrain, the death toll from monsoon-triggered disasters has surged past 252, with 13 new casualties reported in the last 24 hours. What’s unfolding isn’t merely a natural calamity; it’s the latest indictment of the Pakistani state’s chronic failure to prepare for predictable climate-driven disasters, say local officials, environmentalists, and community activists.

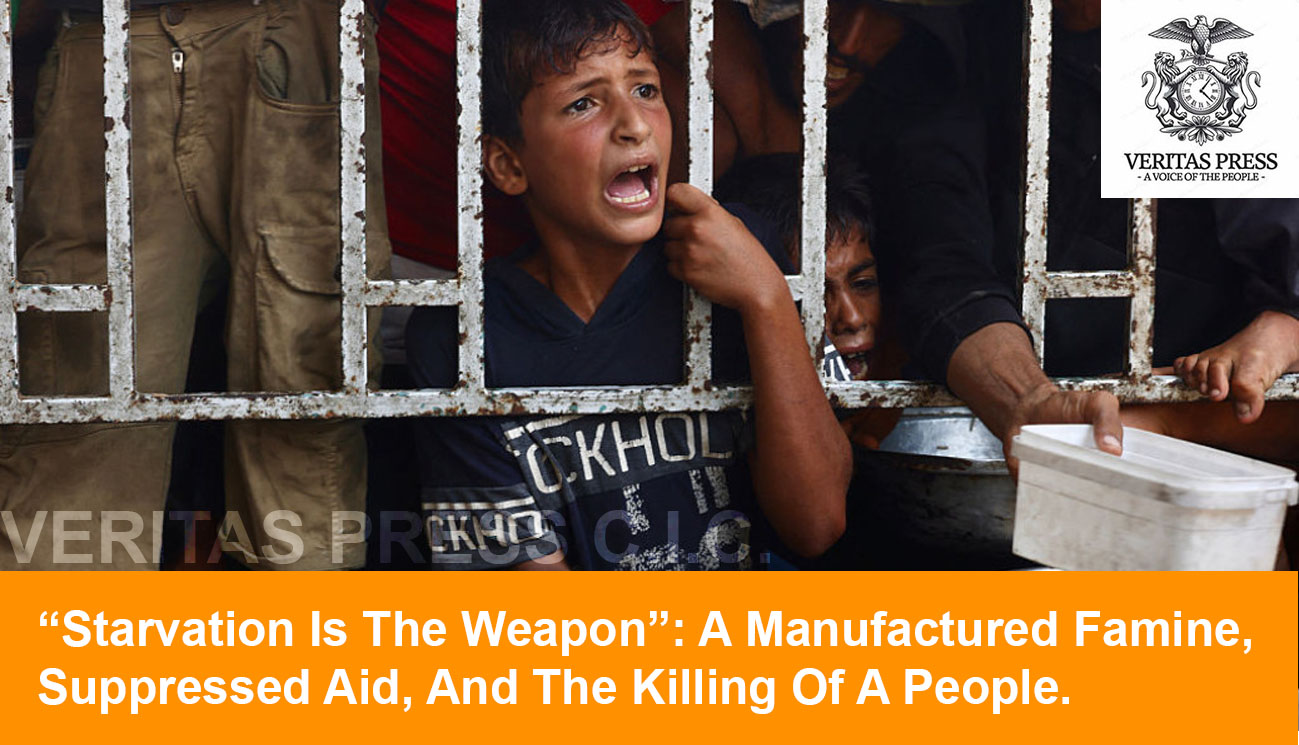

The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) released its latest situation report Wednesday, confirming that since late June, 611 people have been injured, and at least 252 lives lost, including 121 children, in a monsoon spell that has drowned villages, swept away homes, and cut off entire communities.

But to many on the ground, these are not just the tragic consequences of nature; they are symptoms of systemic neglect and state complicity in disaster unpreparedness.

“Every year we beg the authorities to clean drains, reinforce embankments, and clear escape routes. Every year they promise, and every year we bury our children,” said Farzana Bibi, a mother of three from Charsadda whose house was swept away last week in the rising waters of the Swat River.

“A Crisis We Knew Was Coming”:

Despite weeks of advance meteorological warnings by the Pakistan Meteorological Department (PMD), provincial and federal agencies failed to implement robust, pre-emptive evacuation and risk mitigation strategies, critics charge.

“The government had this information weeks in advance. Yet no early warning systems were activated in many remote areas, and emergency services were grossly under-prepared,” said Ahmad Rafay Alam, a Lahore-based environmental lawyer and climate policy expert.

In the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) region, where 13 people, including nine children, died in 48 hours, locals report a familiar pattern: collapsed homes, broken roads, and no state rescue teams for hours or days.

“It was villagers with ropes and shovels who pulled the bodies out of the debris. The government only arrived for photo ops,” said Shakir Khan, a resident of Upper Kohistan, where a woman died after her home caved in.

The KP Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA) confirmed that 19 homes were destroyed or damaged but did not provide a public explanation for the delayed response in the mountainous districts, where terrain difficulties are well known. Analysts suggest this highlights a criminal underinvestment in rural disaster infrastructure.

“It’s not a logistics problem, it’s a priorities problem,” said Zulfiqar Kunwar, a former senior official at the NDMA. “Funds are diverted to vanity infrastructure projects in cities while flood-prone rural districts are left to fend for themselves.”

Tourists Trapped, Roads Washed Out:

In Gilgit-Baltistan, over 200 tourists were trapped earlier this week after flash floods inundated Babusar Highway. All were eventually rescued, but the episode again exposed the fragile state of Pakistan’s disaster preparedness in tourist zones.

“They told us the road was open when it clearly wasn’t,” said Sana Ali, a medical student from Islamabad stranded near Chilas. “We spent two nights without food or phone signals. Local hotel owners sheltered us, not the government.”

Faizullah Faraq, spokesperson for the GB government, admitted parts of the Karakoram Highway remain closed, with “thousands of travellers stranded.” He said “free accommodation” was arranged, but activists say these were mostly ad hoc arrangements made by locals, not the state.

“Once again, ordinary citizens, not the bureaucracy, are the front line of Pakistan’s disaster response,” said Asma Barlas, a disaster relief activist in Gilgit.

Tarbela On The Edge:

Meanwhile, a high alert has been issued at Tarbela Dam, where water levels have surged to 1,530 feet, just 20 feet below the maximum capacity. Officials say power generation is continuing, but experts warn of severe risks.

“Tarbela and other dams are under intense pressure. We’re just one extreme rain event away from a possible overflow disaster,” said Dr. Moazzam Ali, a hydrology expert at NUST. “There’s little redundancy in our water infrastructure system.”

Despite repeated recommendations from national and international climate advisory groups since the 2022 floods, no substantial structural reinforcements have been made at key floodgates, said one NDMA insider on condition of anonymity.

Institutional Paralysis In The Face Of Climate Crisis:

Pakistan’s monsoon season, which typically lasts from late June to September, delivers 70–80% of the country’s annual rainfall, essential for crops and reservoirs. But as climate change intensifies rainfall patterns and increases glacial melt, the same rains have become a source of destruction.

“This isn’t an anomaly anymore. This is a climate emergency playing out every year. Yet the state behaves like each flood is a surprise,” said Aneela Shahzad, a policy analyst at the Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI).

In 2022, record-breaking monsoons submerged a third of Pakistan, killing 1,700+ people, displacing 8 million, and causing $30 billion in damages. Two years later, basic recommendations from post-flood inquiries, like installing real-time river monitoring systems, improving urban drainage, and relocating vulnerable communities, remain largely unimplemented.

“Pakistan is one of the top 10 countries most vulnerable to climate change, but disaster preparedness is treated as an afterthought,” said Maria Iqbal, climate program director at Green Pakistan Coalition. “There is no political will.”

A Gendered Disaster:

The crisis is also disproportionately impacting women and children. Of the 252 reported deaths so far, more than 160 are women or children. In displaced communities, activists warn of growing risks of disease outbreaks, unsafe shelters, and gender-based violence.

“In temporary camps, there are no privacy provisions, no clean toilets, and limited access to healthcare,” said Saima Ashraf, a volunteer in Muzaffargarh, Punjab. “Pregnant women are sleeping in floodwater-soaked tents.”

Despite these glaring issues, the Ministry of Climate Change has remained largely absent from the public conversation. Minister Zartaj Gul has yet to issue a detailed statement or visit the worst-hit areas, drawing sharp criticism.

“When your climate minister is silent during a nationwide climate disaster, you know governance is broken,” tweeted journalist Murtaza Solangi.

Warnings Ignored, Lives Lost:

The PMD issued multiple flash flood advisories over the last week, warning of “very heavy falls” in Kashmir, K-P, Gilgit-Baltistan, Potohar region, and northeastern Punjab. It also forecast heightened risk of landslides, urban flooding, and glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs).

Yet even in Islamabad and Lahore, urban centres with significant media coverage, storm drainage systems have buckled.

“Our drains are choked, our emergency plans outdated. We talk about ‘resilience’ every year and do nothing,” said Rizwan Haider, a civil engineer in Lahore. “We’re in a cycle of denial and destruction.”

Conclusion: A Man-Made Tragedy.

As the monsoon spell continues through July 25, many Pakistanis are bracing for more death, displacement, and devastation. What is unfolding is not just a humanitarian crisis, but a man-made disaster fueled by climate breakdown, state negligence, and elite apathy.

The NDMA, PDMA, and local governments remain reactive, rather than proactive. The structural failures, in governance, planning, and justice, are killing Pakistanis faster than the rain.

“We call these ‘natural disasters’, but there is nothing natural about the failure to act,” said Nadia Rehman, a policy advisor at Oxfam Pakistan. “This is political violence through neglect.”

If Pakistan is to survive the next monsoon, it must stop treating climate-driven flooding as a seasonal anomaly and start treating it as the existential emergency it truly is.

Emergency Helplines:

- NDMA: 1700

- KP Flood Helpline: 1422

- PMD Updates: www.pmd.gov.pk

Tags:

Leave a Reply